|

|

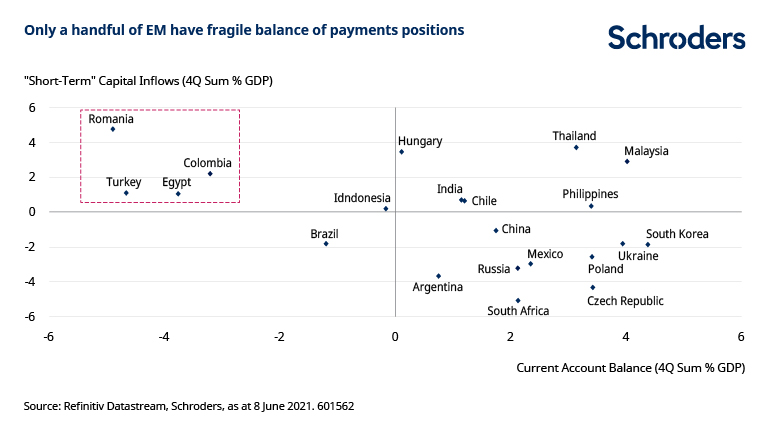

Although the Fed looks likely to tighten policy sooner than previously expected, the 2013 “taper tantrum” should be avoided. But tapering will still have a variety of implications for emerging markets. In our latest Economic and Strategy Viewpoint, we brought forward our expectations for Federal Reserve policy tightening. We still think that the current bout of inflation in the US will prove to be largely transitory. However, the strength of the US economic recovery means that we now expect underlying price pressures to build next year such that policymakers will need to act sooner. As a result, we now expect the Fed to begin tapering its asset purchases under its quantitative easing (QE) program by the end of this year, and to begin raising interest rates at the end of 2022. This is more hawkish than is currently priced into US rates markets. The implication of our view that the Fed will begin to reduce its asset purchases by year-end is that policymakers will need to turn decisively hawkish in the near future. The usual chronology for changes in policy direction is that the Fed will first need to first signal that it is considering thinking about tapering. This is before it can move on to actually announcing it (perhaps in September) and finally trimming purchases later in the year. Why a repeat of the 2013 taper tantrum is unlikelyThis immediately brings back memories of the now infamous taper tantrum that rocked financial markets in the emerging world in 2013. The then governor of the Fed, Ben Bernanke, sparked a 100bps increase in the 10-year Treasury yield after he caught investors off-guard by telling Congress that asset purchases could be reduced. Fears of higher risk-free rates in the US sparked capital flight from emerging markets (EM). And this exposed large external imbalances and ultimately forced central banks to raise interest rates in order to calm volatility in the financial markets. There are good reasons to think that an exact repeat of the 2013 taper tantrum will be avoided. Most obviously, policymakers will be keen not to follow in the footsteps of Bernanke in upsetting the applecart, and are likely to be more cautious in approach and communication. Meanwhile the idea of tapering is no longer alien to markets. Indeed, investors are already speculating about its timing. And as we argued earlier this year, the macroeconomic backdrop in EM is somewhat different: tepid inflows of “hot money” mean that there is not such a large overhang of positioning by foreign investors, and the COVID-19 crisis has cleaned up the balance of payments in most economies. Indeed, as the chart below shows, only a handful of EM have large current account deficits that rely on short-term funding which was the crux of the “fragile five” in 2013. |

|

| EM assets overcame a wobble earlier this year

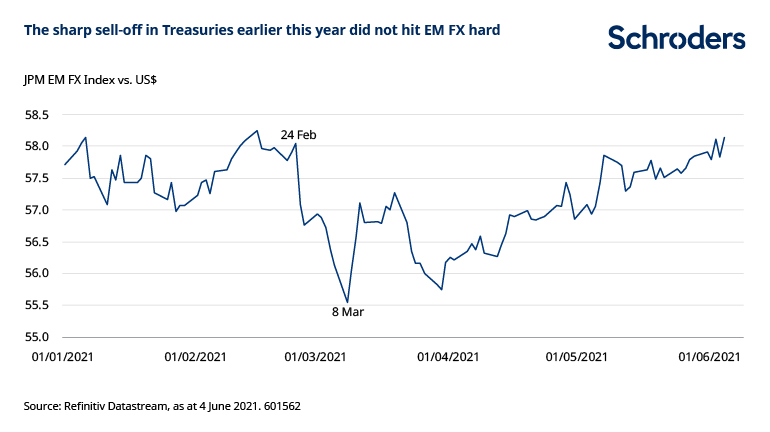

Improved fundamentals probably explain why, despite a bout of volatility in markets, EM assets were able to largely withstand the sharp sell-off in Treasuries earlier this year. The 10-year Treasury yield rose by about 80bps in the first quarter of this year to 1.72%, which was the third worst sell-off on a total return basis in history. But while that led to some wobble in EM financial markets, the magnitude and duration of those losses were small. For example, the JP Morgan Index of EM currencies against the US dollar fell by just 2.5% between 24 February and 8 March. That was only a fraction of the losses suffered in 2013 when the index dropped by about 10%, while all of the losses earlier this year have been recouped on average. |

|

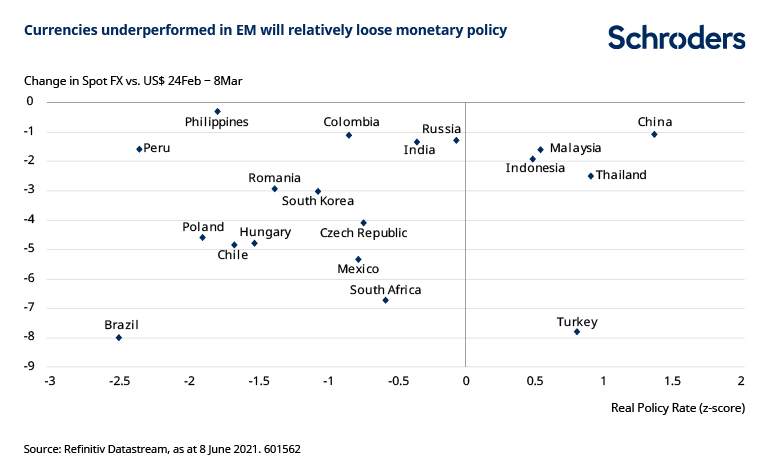

| As is always the case in EM, there was a wide dispersion of the relative performance of currencies within the JP Morgan Index. While some currencies such as the Chinese renminbi and Russian rouble weakened by only about 1% against the US dollar, others such as the Brazilian real, South African rand and Turkish lira dropped by as much as 8%.

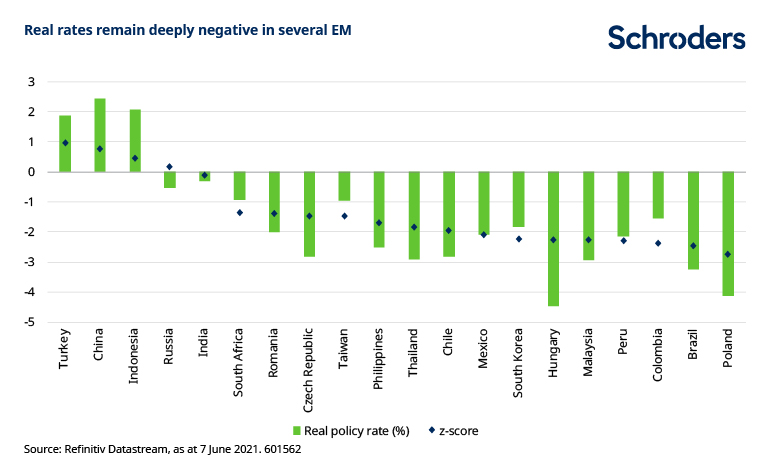

There was a lot going on during that period and for example Brazilian markets also had to contend with high and accelerating new numbers of Covid-19 infections that also appeared to weigh on the performance of assets. However, it does seem that there was some underperformance of markets that had historically low real interest rates when the sell-off in US Treasuries began to hit sentiment towards EM. |

|

|

Perhaps giving credence to this pattern, it has been noticeable that the Brazilian real has begun to perform well since the central bank started to tighten monetary policy aggressively and signaled that future hikes are likely to follow in the months ahead. Real rates in Brazil remain deeply negative both on an actual and historical basis, but this hawkish forward-guidance may spare the currency some pain if the Fed pivots. Where EM markets are most vulnerable? |

|

| If markets do focus on real rates, then it seems that currencies in EM such as Colombia and Peru could come under greater scrutiny. Both markets also face political uncertainty, while Colombia’s external position is also weak.

This could force central banks to turn more hawkish. And a positive real interest rate it Turkey is unlikely to save the lira completely, given that the balance of payments are relatively poor and President Erdogan has been calling for what would probably prove to be premature interest rate cuts. |

|

| Schroders is an Associate member of TEXPERS. The views and opinions contained herein are those of Schroders' investment teams and/or Economics Group, and do not necessarily represent Schroder Investment Management North America Inc.'s house views. These views are subject to change. This information is intended to be for information purposes only and it is not intended as promotional material in any respect. Follow TEXPERS on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn as well as visit our website for the latest news about Texas' public pension industry. |

Jun

29

Share this post: